Sukarno

Collector & Patron of Modern Indonesian Art

Lecture — Aug 30, 2018 — Mikke Susanto

I have been formally conducting research about Sukarno since 2008. Over the course of my research, I have found many stories about Indonesian art, Sukarno, and his art collection. My research has been conducted not only in the six President Palaces and with Sukarno's family, but also at the homes of more than twenty artists in Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Bali, and Bandung. My research has produced four exhibitions, seven articles and four books, as well as a private collection of more than two hundred photographs about Sukarno and his art collection.

Sukarno, recognized as the proclaimer of Indonesia's independence (1945) and the driving figure behind several events in international politics, was also fond of art and an ardent lover of paintings. His collection was the number one painting collection in Indonesia. As an art collector, he left behind a massive collection of paintings, sculptures, and other kinds of art objects. By the end of his presidency, he had amassed more than 2,300 artworks in his collection.

Sukarno had a habit of giving the works in his art collection marks of ownership. He would order someone from the palace staff, for example an adjutant or palace painter (often Dullah or Gapoer), to make a notation on the back of paintings. As a result, the paintings do not only have these obvious marks, but they also tell stories. These stories are not just about the persons who wrote on the back of the canvases, but also refer to a number of remarkable issues.

During my research, the texts on the back of each painting in Sukarno's collection invited me to travel through space and time to bring together historical stories while uncovering other, possibly unexpected, sides of Sukarno. These stories are as meaningful and important as the paintings themselves: they contain history, originality, and value. Texts like the ones on the back of the paintings gently stirred me to explore the collection of the Presidential Palace of the Republic of Indonesia.

Sukarno's Artistic Skills

From childhood on, Sukarno (born 1901) enjoyed drawing. It was a common activity of his while he lived in Mojokerto between 1907 and 1916 and studied at the Eerste Inlandse School (EIS). This can be read in his biography by Cindy Adams, who retold his story in a chapter on Sukarno's imprisonment in Banceui, Bandung. Sukarno mentioned that he had been lonely in prison, and therefore had regularly shared wayang stories with Gatot, a fellow nationalist who was held three cells over.1

One time, during class, a drawing contest was held. Of all the students, Sukarno was the first to finish his work. His teacher praised him, not because of the speed but because of the quality of his work; his was the best drawing produced in the class. However, his score was not the highest; that honor was granted to a Dutch student. As he later told Cindy Adams, Sukarno was enraged by this injustice.2

Hermen Kartowisastro writes that Sukarno was one of the best artists at HBS Surabaya.3 According to Kartowisastro, in 1917 he and a group of friends were approached by Sukarno upon returning to school after the holiday. He showed them one of his works, a watercolor landscape of rice fields, rivers, and hills. Although Kartowisastro considered this work to be nothing special, this incident emphasized that Sukarno had been more interested in creative activities than his fellow students were.

Sukarno's eldest son, Guntur Sukarno, wrote briefly about his father's hobby.4 Guntur wrote that his father, in his teenage years, had been a good artist, drawing and painting wayang figures, buildings, airplanes, ships, and landscapes. He used his artistic skills to earn some extra spending money. While at HBS, Sukarno often drew wayang figures to sell to Dutch people; his favorite figures to draw were Raden Gatotkaca and Pangeran Purbaya. Sukarno would also draw European stories, such as the Three Musketeers, Gulliver’s Travels, Tarzan, Robinson Crusoe, and David and Goliath. Other frequent subjects of his were historical figures such as Diponegoro, Patimura, and Sentot Alibasyah. All of these drawings and paintings he sold to Dutch customers.

Formal "Art" Education

Sukarno only received a formal introduction to art while studying at the Department of Civil Engineering, Technische Hoogeschool (now the Bandung Institute of Technology). Although this was not a visual arts program, it may still be considered a place where one could study drawing in an academic context. At the time, engineering programs taught not only how to plan civil engineering projects, but also how to draw and paint buildings, bridges, and other works of civil engineering. His academic training in civil engineering and architecture did not only influence Sukarno's choices of medium and techniques for painting, but — according to Sukarno himself — also influenced his teachers at TH Bandung.5

It should be noted that Sukarno studied under Prof. Charles Prosper Wolff Schoemaker, a professor of architecture and celebrated architect of the early 20th century. He was highly communicative, and opened his mind to insights from the indigenous community. He got along famously with Sukarno, who was then only 20 years of age. Both were skilled at architecture, sculpture, and beautiful women. Schoemaker offered drawing lessons at his home; Sukarno was his student. During this time, Sukarno produced several watercolors.6

Art and Politics

On 26 July 1926, Sukarno officially became a civil engineer. He established an engineering agency together with his classmate, Ir. Anwari. Here, he produced several architectural works, including Hotel Preanger in Bandung. While working as an architect, Sukarno continued to paint. As his subject he took the West Java landscape.7

Sukarno's paintings appear technically mature, taking a naturalistic style. One of these is a watercolor titled Tjoeroeg Tjikaso (Cikaso Waterfall).

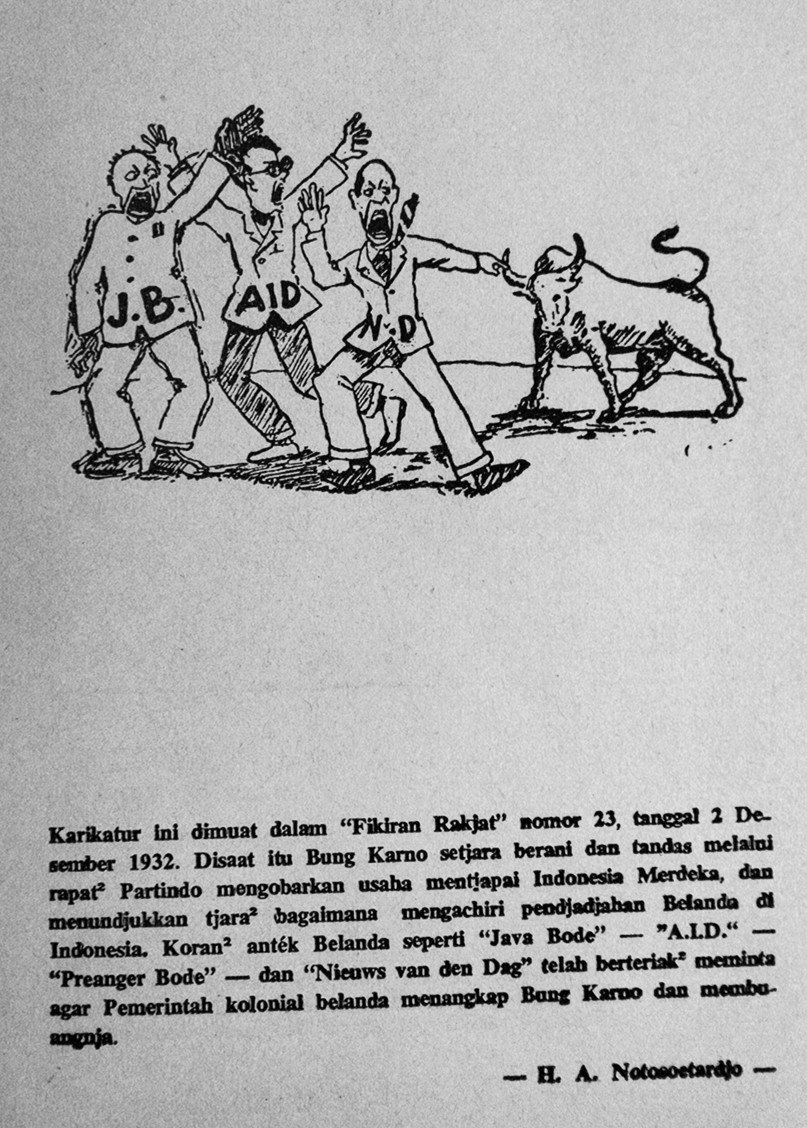

Because of his close involvement in the nationalist movement, Sukarno ultimately decided to leave architecture behind. While he continued to paint, he also involved himself in the anti-colonial struggle through his speeches, writings, and diplomacy, as well as by establishing the Partai Nasional Indonesia (Indonesian National Party, PNI). As a result he was frequently imprisoned, including in Banceui and Sukamiskin, Bandung. While in prison, Sukarno completed a number of caricatures that were published in Fikiran Ra'jat. He completed these caricatures under the alias Soemini.8

On 28 July 1932, after leaving prison, Sukarno took control of Partai Indonesia (Indonesian Party, Partindo). At this time, he was receiving a wage of 70 rupiah per month. Sukarno also received money from Fikiran Ra'jat, the newspaper he had founded in Bandung. His political activities continued unfettered. He traveled regularly, delivering speeches to approving crowds. He disturbed the Dutch colonial government most with his brochure "Mentjapai Indonesia Merdeka" (Realizing a Free Indonesia). This brochure was taken as incitement, and its publication and distribution were prohibited. Homes were searched, while gatherings of more than three people were disbanded. Ultimately, one evening, when Sukarno was to hold a meeting at the home of Husni Thamrin in Batavia (now Jakarta), he was arrested by the authorities.

Held without trial, Sukarno and his family were exiled to the town of Ende in Flores (now part of East Nusa Tenggara Province) on 17 February 1934.9 This exile introduced Sukarno to a life of loneliness and silence. He saw Flores as uncivilized, without any form of (access to) public facilities. Initially, he felt himself living under pressure, his life full of stress. However, Ende also offered him the opportunity to further develop his hobby. Ende was a catharsis for Sukarno, as he continued painting and established a theater group. This group, given the name "Kelimutu", performed works penned by Sukarno himself. As no other artists lived in the town, Sukarno also handled the scenography for the group's performances.10

According to Giebels, to support his hobby, Sukarno ordered painting and drawing supplies from Surabaya. This is not surprising; Sukarno's monthly income of 150 guilders was more than enough to live in Ende, and thus he had sufficient disposable income to acquire art supplies.11 Some of these supplies, including his pencils, palette, and easel, are still held at the Sukarno’s House in Ende.

One of his best works is Pantai Flores (1934–36), a watercolor on paper measuring 44 x 60cm. Another work from this period, Kampung Ambugaga (1936), is presently held by a collector in Surabaya. Both works show harmony and ecology, reflecting Sukarno’s concept of the cosmos. His technique and use of watercolor indicate skill, showing that over the course of his lengthy exile Sukarno gained considerable mastery of this difficult medium.12

Patronage and Aesthetic Consciousness

For unspecified reasons, Sukarno and his family were moved to Bengkulu, Sumatra in 1937.13 There, Sukarno could move more freely as an architect, for example by renovating an old mosque now known as Masjid Jami.

In 1942, during World War II, Indonesia was occupied by Japan. During this time, Sukarno was brought back to Batavia. For many Indonesians, this created a multi-dimensional crisis. The situation was different, however, for the visual arts, which grew rapidly. Aside from introducing new security and political policies, the Japanese occupation government introduced new cultural policies.

Several organizations, political and otherwise, were disbanded. The Bataviasche Kunstkring, which had been in charge of introducing western culture during the Dutch colonial era, was shut down by the Japanese. Persagi (Union of Indonesian Artists, Persatuan Ahli Gambar Indonesia), under the leadership of Agus Djaja, was also disbanded. Such steps were taken to create social change in Indonesian society.14

Through the Sendenbu (Propaganda) Department, the Poesat Tenaga Rakyat (Center for the People's Labor, Poetera) was established on 9 March 1943.15 This new organization was intended not only to transform the mentality of the Indonesian people (as similar agencies had been doing in Taiwan and Korea), but also to mobilize the Indonesian people and promote Japanese interests.

Poetera was used by the Indonesian people to increase political awareness among nationalist groups. The Japanese government recruited a number of nationalist leaders, including Sukarno (as chair), Mohammad Hatta, Ki Hadjar Dewantara, and Kyai Haji Mansoer to manage the organization.16 Several Japanese served on the organization's council. Poetera's office, located on Jalan Bunda Theresa in Jakarta, opened on 16 April 1943. It included four departments, responsible for organizations, culture, propaganda, and public health. The department of culture was under the leadership of famed Indonesian artist S. Sudjojono.

This was a significant introduction in the context of Sukarno's relationship with art, an introduction one that amounted to a formal institutionalization. It shaped Sukarno's tastes, which were later manifested in his collection of art both as president and as an individual.17

As the chairman of Poetera, Sukarno was able to purchase paintings and begin collecting them, an activity that was supported by his wages as chair of Poetera.

While in Indonesia, the Japanese government established a number of other organizations, including Jawa Hoso Kanrikyoku (Javanese Broadcast Bureau), Jawa Shinbunkai (Javanese Newspaper Corporation), Domei (News Agency), Jawa Engseki Kyosai (Javanese Union of Drama Groups), Nihon Eighasa or Nichi'ei (Japanese Film Corporation), and Eiga Haikyusha or Eihai (Film Distribution Corporation). It also established an organization focused exclusively on arts and culture that "competed" with Poetera. This organization was Keimin Bunka Shidōsho, the "Cultural Center", established in April 1943 and located at Jl. Noordwijk 39, Jakarta. This organization included a number of legendary artists, including Sanusi Pane (literature), Agus Djaja (visual arts), Usmar Ismail (film), Koesbini (music), and Djauhar Arifin (theater).18

As with Poetera, Keimin Bunka Shidōsho recruited numerous artists and sponsored a number of exhibitions. These included exhibitions held in Java's major cities (fourteen by 1944, according to the newspaper Asia Raya). The Cultural Bureau also organized painting classes, taught by Agus Djaja together with such artists as Wahdi, Barli, Affandi, and Hendra Gunawan.19 In these exhibitions, Sukarno, together with other nationalists and artists, sought to foster a sense of togetherness and thereby promote Indonesia's struggle for independence.

In these exhibitions, Sukarno, together with other nationalists and artists, sought to foster a sense of togetherness and thereby promote Indonesia's struggle for independence.

In the days following the proclamation of Indonesia's independence, on 17 August 1945, Sukarno remained active. In a "secret space" in Balai Pustaka, Central Jakarta, he sought to promote the struggle. Sukarno asked Sudjojono to ensure that artists produced a number of pro-revolution posters. Sudjojono then sought the support of Balai Pustaka's leadership, as it was frequently responsible for graphic design. For this poster, Balai Pustaka hired Affandi, who took the artist Dullah as his model. Depicting a powerful and shouting revolutionary, waving Indonesia's red-and-white flag, this 30 x 35 cm poster is otherwise empty, without any text.

Between his other activities, the poet Chairil Anwar was tasked with writing text for this poster. Thus "Boeng, Ajo Boeng!" (Guy, Come on Guy) was born. According to Sudjojono, such a phrase was common among the contemporary Indonesian people. It was used, for example, by prostitutes to attract the attention of men desiring their services. This poster was reproduced by Abdulsalam, Suwiryo (then the Mayor of Jakarta), Suromo, and other artists, to be distributed throughout the republican territory. Sukarno was greatly moved by this provocative poster, and asked Sudjojono who the model was. Sudjojono answered simply: “Dullah”. Hearing this name, Sukarno was tickled, "Dullah? Belanda pasti tidak menyangka bahwa model dalam poster itu orangnya kecil. Kecil!" ("Dullah? The Dutch would never guess that this poster's model is so tiny. Tiny!”)20

Sukarno planned for the establishment of an art museum, shortly after the nation was proclaimed.

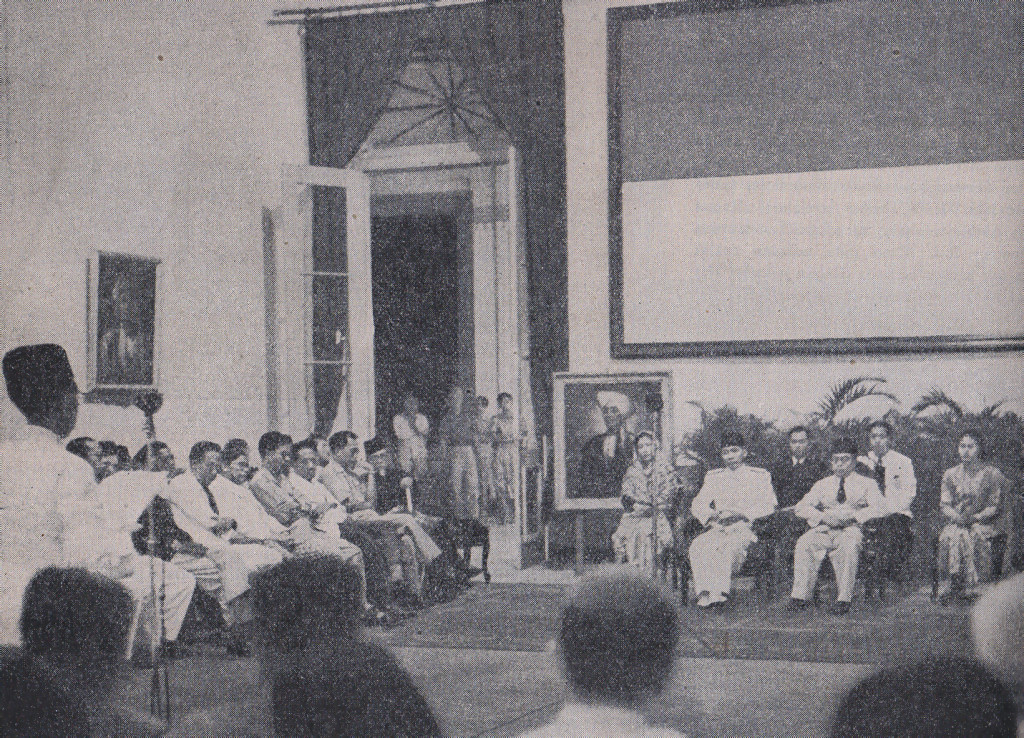

Furthermore, Sukarno asked painters to create portraits of Indonesia's heroes. No written documentation of this duty has been found. However, authentic evidence is presented by these paintings and photographs of these paintings on display. Some were used in formal activities while Sukarno lived at Gedung Agung—the Yogyakarta palace. The first shows a ceremony commemorating the second anniversary of Indonesia's independence, with Sukarno sitting together with Fatmawati and Mohammad Hatta, listening to a report by the committee chairman Ki Hadjar Dewantara. Behind them stands Potret Pangeran Diponegoro, while the painting Potret Tengku Tjikditiro hangs on the wall. Information on the second photograph is lacking. It was, however, likely taken in the same year, at a different event. This photograph appears to depict a formal event in the main hall of Gedung Agung, again with Potret Pangeran Diponegoro behind him, sitting on an easel.

It appears that Sukarno did not order only these two portraits. Presently, twelve such paintings are held in the collection. They remain in good condition, although they require special treatment. These were produced by such artists as S. Sudjojono, Affandi, Suromo, Harijadi S., Trubus S., Sudarso, Dullah, and Surono. Most of these portraits, which decorate the palace walls and preserve the memory of the nation, used a realistic approach and reflect the artists' personal styles.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Sukarno continuously and intensely sought to fill his presidential palaces with artworks. He not only brought the works held at his home on Jalan Pegangsaan Timur, which he had collected before he became president, but also carried with him the works he acquired in Yogyakarta. His relationships with artists ensured that numerous new works entered the palace collection. His presidential activities and his negotiations with the leaders of other nations likewise contributed importantly to the collection's growth. Often, while returning home from a trip abroad, he would bring home works of art. It is thus hardly surprising that, in these three decades, Sukarno was able to collect more than a thousand artworks.

This means that, for three decades, Sukarno motored modern Indonesian art as best as he could. His patronage was characterized by, among others:

- Painting and drawing caricatures as part of the development of his personal ideas and as an expression of the political struggles of the nation.

- Helping found arts organizations and creating a legal umbrella for them so they could become part of the struggle for independence or a means to develop patriotism and nationhood, as with Poetera during the Japanese occupation era.

- Visiting studios, art academy, galleries, museums, and exhibitions; both at home and abroad, including the attendance of opening/inaugurating exhibitions of fine arts and visiting as an ordinary guest.

- Recruiting painters as co-workers and managers of art objects in the Presidential Palace.

- Inspiring and suggesting ideas to artists (painters, sculptors, poster artists, photographers), and initiating art exhibitions.

- Frequently purchasing works of art at exhibitions and studios.

- Commissioning artworks (paintings, murals, reliefs, statues/monuments) for private and state needs.

- Having meals and discussions with artists and their families at the Presidential Palace.

- Inviting artists to travel to sites to ask for their opinions, for example, for drawing the Garuda Pancasila (national logo), establishing airports, creating monuments, using certain places for recreational purposes, etc.

- Saving artists from imprisonment or death for ideological reasons.

- Sitting as a model for sketches, paintings, sculptures, and photographs.

- Regularly reviewing his collection and displaying Palace artworks.

- Providing information about artworks to palace guests, both domestic and international.

- Using artworks as backdrops for state ceremonies/events as well as photos with state guests.

- Watching artists at work and giving critical commentary when considered necessary.

- Supporting the establishment of galleries and inviting guests to visit and appreciate them, and even encouraging guests to become collectors.

- Recommending artists to travel or reside abroad.

- Bringing artworks as souvenirs from abroad and vice versa.

- Making the palace a museum of art.

- Publishing high quality books on his collections so that works could be appreciated widely, even if only as photographic reproductions.

Conclusion: Sukarno and Artists

Circumstances in 1950s Indonesia were highly distinctive. Sukarno, as a revolutionary leader, proclaimer of Indonesian independence, and President helped shape them in his own way. Sukarno, who loved beauty, also liked to see himself very much, as can be observed particularly in photographs. Sukarno was very fond of the camera, and his various activities—including his meetings with artists—were therefore never far away from photographers' lenses. A heap of anecdotes, archives, and photographs seem to suggest that Sukarno indeed lived in two worlds: politics and the arts.21

Sukarno made many good choices. Most works in his collection have become important in the history of Indonesian art, and the artists are being recognized as maestros in the Indonesian and Asian art worlds. My research has revealed just how Sukarno lived at the dawn of modern Indonesian art. To some extent, it may be said that Sukarno lived on the vanguard of early Indonesian art. Most prominent figures in Indonesian art were born at the turn of the century, i.e. the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century. Artists born around that time include Affandi (1907), S. Soedjojono (1913), Agus Djaja (1913), Lee Man-fong (1913), Sudarso (1914), Basoeki Abdullah (1915), Hendra Gunawan (1918), Dullah (1919), Harijadi Sumadidjaja (1919), Henk Ngantung (1921), Barli (1921), Sudjana Kerton (1922), Trubus Soedarsono (1926), Edhi Sunarso (1932) and others. In Bali, there were Le Mayeur (1880), Rudolf Bonnet (1895), Auke Sonega (1910), Ida Bagus Nadera (1910), Ida Bagus Made Widja (1912), Ida Bagus Made Poleng (1915), Ketut Kobot (1917), and Renato Cristiano (1926).

Therefore, Sukarno's rise coincided with the development of modern art in Indonesia. He and the aforementioned artists worked shoulder to shoulder to build Indonesia. In addition to working for themselves, these artists performed tasks for the State (represented, in this case, by Sukarno). During the pre-independence period, they worked on posters and running exhibitions. In the time immediately following Indonesia's proclamation of independence, they personally explored the meaning of freedom and expressed it through their art.

Generally, these artists came to know Sukarno in the pre-independence era. Most met him during the Japanese occupation, with the exception of Basoeki Abdullah, who had known Sukarno since the 1930s. During the Japanese occupation, he and Sukarno became closer, as they belonged to the same organizations: Poetera and Keimin Bunka Shidōsho. They interacted intensely, both on a personal and an organizational level. As such, during this time they must have learned about each other. The situation was different for artists based in Bali, with whom Sukarno began to become acquainted in the 1950s. Sukarno's relationships with these artists became more intense when he was building the Tampaksiring Palace, and they were reinforced by Sukarno's visits with State guests and vacations in Bali.

These artists' close relationships with Sukarno through the 1960s clearly showed on the occasions when Sukarno invited them to the palace, particularly those artists based in Java. Dullah immediately came to "live under the same roof" with Sukarno for some ten years. While other painters were invited to dine at the palace and discuss artworks, Dullah was tasked with many things by Sukarno, including painting, maintaining art objects, and taking pictures of Sukarno's daily activities. Dullah became Sukarno's "shadow".

The 1950s and 1960s appear to have been the golden age for Sukarno's relationship with artists. The decade saw such relationships growing increasingly intense, as evident in the president's visits to artists' studios and art exhibitions. This was also the decade when Sukarno asked the national leaders of various countries to give Indonesian artists the opportunity to go abroad. Sukarno's affinity with artists delighted them most when Sukarno bought their works. Within a decade, Sukarno had acquired about a thousand modern Indonesian artworks.

In the early 1960s, Sukarno continued to collaborate with artists, recruiting a number of them to take part in the creation of several monuments in Jakarta. These included Monumen Nasional (the National Monument), Patung Selamat Datang (the Welcome Statue, near the Hotel Indonesia traffic circle), Tugu Dirgantara (at Pancoran), and the Pembebasan Irian Barat Monument (at Banteng Square), as well as various esthetic elements of such prestigious hotels as the Hotel Indonesia, Hotel Ambarrukmo, Bali Beach Hotel, and Samudera Beach Hotel.

The political turmoil of the 1960s in Indonesia peaked in September 1965. Following this year, Sukarno experienced severe challenges and difficulties. Until his death in 1970, he remained separated from artists, an experience that saddened him greatly. Some adjutants said that he was allowed to associate with art only in the palace. The worst, thus, came in 1967 when the sick president was ordered to leave the palace and move to Wisma Yaso building, Jakarta. There he had to stay under city arrest, and not everyone was permitted to visit him. Sukarno told his children to bring nothing but clothing with them when leaving the palace. As such, the artworks he collected were fully intended to become everlasting residents of presidential palaces.

About the author

Mikke Susanto is a lecturer at the Faculty of Art, Indonesian Institute of Art (ISI), Yogyakarta. His art criticism has been published in mass media and several journals. He also works as an independent curator, having handled more than 100 exhibitions in Indonesia as well as abroad. In 2009, he was appointed as a curatorial consultant for the Museum of the Presidential Palace of Indonesia, and he has often been consulted regarding museum matters and exhibition management. Since August 2017, he has been an acquisition committee member at the National Gallery, Singapore. Susanto has published more than 40 books, including: Sukarno's Favorite Painters (2018); JEIHAN: Maestro Ambang Nyata dan Maya (KPG, 2017); 17/71: Goresan Juang Kemerdekaan: Koleksi Benda Seni Istana Kepresidenan Republik Indonesia (2016); BUNG KARNO: Kolektor & Patron Seni Rupa Indonesia (2014); MAESTRO Seni Rupa Modern Indonesia (2013).

This article was translated by Christopher Woodrich, 11 June 2018.

Notes

1. Cindy Adams, Bung Karno, Penjambung Lidah Rakjat Indonesia (Jakarta: Gunung Agung, 1966), 134.

2. Adams, 59.

3. Hermen Kartowisastro, “Pemuda Sukarno, Kawan Sekolah dan Kawan Mainku Selama 1909–1919”, in Hero Triatmono (ed.), Kisah Istimewa Bung Karno (Jakarta: Kompas, 2010), 15–17. HBS is Hogere-Burgerschool, a five-year senior high school in the Dutch Indies during the colonial era.

4. This general overview of Sukarno and his collection process has been assisted by Guntur Sukarno, Bung Karno dan Kesayangannya (Jakarta: PT. Karya Unipress, 1981), 187–217.

5. Adams, 92.

6. Lambert Giebels, Soekarno Biografi 1901–1950 (Jakarta: Grasindo, 2001), 56.

7. I must express my gratitude to Djuli Djati Prambudi, who wrote a book dealing specifically with Sukarno's works and collection, Bung Karno, Seni Rupa dan Karya Lukisnya (Surabaya: Laskar Budi Utomo, 2001), 46.

8. These caricatures were collected and included in a two-volume set of books that is required reading for those seeking to understand Sukarno's thoughts, Dibawah Bendera Revolusi (Jakarta: Dibawah Bendera Revolusi Publication Committee, Volumes I and II, 1956/1961/1964/1965).

9. Giebels, 194; Bernhard Dahm, Soekarno dan Perjuangan Kemerdekaan (Jakarta: LP3ES, 1987), 218.

10. Adams, 176.

11. Giebels, 197. Furthermore, according to Giebels, through his closeness with these missionaries, Sukarnogained access to books and supplies. These missionaries appear to have recognized Sukarno as an intellectual and artist.

12. Adams, 170.

13. Giebels, 216.

14. M. Agus Burhan, “Paradoks dalam Seni Lukis Indonesia Masa Jepang”, Academic Speech (Yogyakarta: Committee of the XX Anniversary of ISI Yogyakarta (Lustrum IV)), Jumat 23 July 2004.

15. Many stories circulate regarding the establishment of Poetera. The date included here is that given by Bernard Dahm, p. 294. Giebels, meanwhile, gives 8 March as the founding date of Poetera. Some sources mention 1942, while others state 1 March 1943. Contemporary sources are similarly unclear. Djawa Baroe No. 5 states 1 March 1943, while Djawa Baroe No. 1, dated 1 January 1943, states 8 December 1942, commemorating the first anniversary of the Greater East Asia War and Poetera's first exhibition. The writer has been greatly helped in this by a footnote in Aminudin Th. Siregar, Sang Ahli Gambar: Sketsa, Gambar & Pemikiran S. Sudjojono (Jakarta: S. Sudjojono Centre & Galeri Canna, 2010), 387.

16. According to Bob Hering, the empat serangkai (Gang of Four) began to take shape when Sukarno visited Yogyakarta in 20–22 July 1942 and stayed at the home of Ki Hadjar Dewantara. See Bob Hering, Sukarno Bapak Kemerdekaan Indonesia Sebuah Biografi 1901–1945 (Jakarta: Hasta Mitra, 2003), 341.

17. This “formal” introduction is mentioned in Wiyoso Yudoseputro, "Bung Karno dengan Seni”, in Soedarmadji J.H. Damais, Bung Karno dan Seni (Jakarta: Yayasan Bung Karno, 1979).

18. M. Agus Burhan, 267.

19. M. Agus Burhan, 9.

20. Agus Dermawan T., "Bung Karno dan Tiga Pelukis Istana”, Kompas, Friday, 1 June 2001.

21. Lim Wasim, the Presidential Palace Painter from 1961–1968, admitted: “His closeness with painting was equal with his involvement in politics, with his nation, with his people. History has to mention that he was the first person to trigger painting collecting in Indonesia.” in Agus Dermawan T., Lim Wasim, Pelukis Istana Presiden (Jakarta: Yayasan AiA, 2001), 27.

Bibliography

- Adams, Cindy, 1966, Bung Karno, Penjambung Lidah Rakjat Indonesia. Jakarta: Gunung Agung.

- Burhan, M. Agus, 2004, "Paradoks dalam Seni Lukis Indonesia Masa Jepang", Academic speech, Yogyakarta: Committee of the XX Anniversary of ISI Yogyakarta (Lustrum IV)), 23 July.

- Dahm, Bernhard, 1987, Soekarno dan Perjuangan Kemerdekaan, Jakarta: LP3ES.

- Dermawan T., Agus, 2001. "Bung Karno dan Tiga Pelukis Istana", Kompas, 1 June.

- Dermawan T., Agus, 2001, Lim Wasim, Pelukis Istana Presiden, Jakarta: Yayasan AiA.

- Giebels, Lambert, 2001, Soekarno: Biografi 1901–1950, Jakarta: Grasindo.

- Hering, Bob, 2003, Sukarno, Bapak Kemerdekaan Indonesia Sebuah Biografi: 1901–1945, Jakarta: Hasta Mitra.

- Kartowisastro, Hermen, 2010,"Pemuda Sukarno, Kawan Sekolah, dan Kawan Mainku Selama 1909–1919", in Hero Triatmono (ed.), Kisah Istimewa Bung Karno. Jakarta: Kompas.

- Prambudi, Djuli Djati, 2001, Bung Karno, Seni Rupa dan Karya Lukisnya, Surabaya: Laskar Budi Utomo.

- Siregar, Aminudin Th., 2010, Sang Ahli Gambar: Sketsa, Gambar & Pemikiran S. Sudjojono, Jakarta: S. Sudjojono Centre and Galeri Canna.

- Sukarno, 1956/1961/1964/1965, Dibawah Bendera Revolusi, Jakarta: Dibawah Bendera Revolusi Publication Committee, Volumes I and II.

- Sukarno, Guntur, 1981, Bung Karno dan Kesayangannya. Jakarta: Karya Unipress.

- Yudoseputro, Wiyoso, 1979, "Bung Karno dengan Seni", in Soedarmadji J.H. Damais, Bung Karno dan Seni, Jakarta: Yayasan Bung Karno.