Try to Overstand

Longread — Sep 2, 2020 — Tirdad Zolghadr

In the Presence of Absence is an impressive array of “stories and (counter) narratives” that pursue forms of knowledge underrepresented within public debates. The overall curatorial effort that questions “how we know what we know” led to this writing commissioned to address the epistemology of Contemporary Art.

Epistemology derives from the Greek epistasthai: “knowing how to do or understand.” The term Epi (“above”) initially suggested not an under-standing but an over-view or, literally, an “over-standing.” Now as an art writer and occasional curator, the best I can offer is not an over-view from the Greeks onward, but to position myself on a level playing field with commissioners and artists. Even if I draft hypotheses on knowledge production qua Contemporary Art exhibitions in general, the hypotheses are based on my own experience in circulating, mediating, and curating. On the one hand, I’d like to spare myself phone calls to nerdy friends who would need to double check my statements on Plato. On the other, such a curatorial perspective already embodies an example of how knowledge is produced within and via Contemporary Art – specifically.

To be clear, I myself have never had qualms about outsourcing tough talk to scholars, to sociologists or historians who objectify art without shame. But there is an advantage to the embedded criticality of writer-curators who speak from a position more or less on par with the artworks themselves. When art is deployed as material along extrinsic parameters (critico-theoretical, historico-philosophical, etc.), one loses sight of what makes art distinctively interesting to begin with. Often, it is unclear why the artworks used to make that academic point was not graphic design instead, or billboards, or the weird book covers of academic publishing itself.

So, if I am wobbly with my Greeks, I do know the tricks of the trade that allow Contemporary Art to get away with murder. A visitor from the philosophy department of University of Paris VIII Vincennes – Saint Denis would give you a more solid take on knowledge production – by means of what is coincidentally an art show, but with rather less patience for the macropolitics and microhistories that set art shows apart from traditions such as the philosophical, the theoretical, and so on.

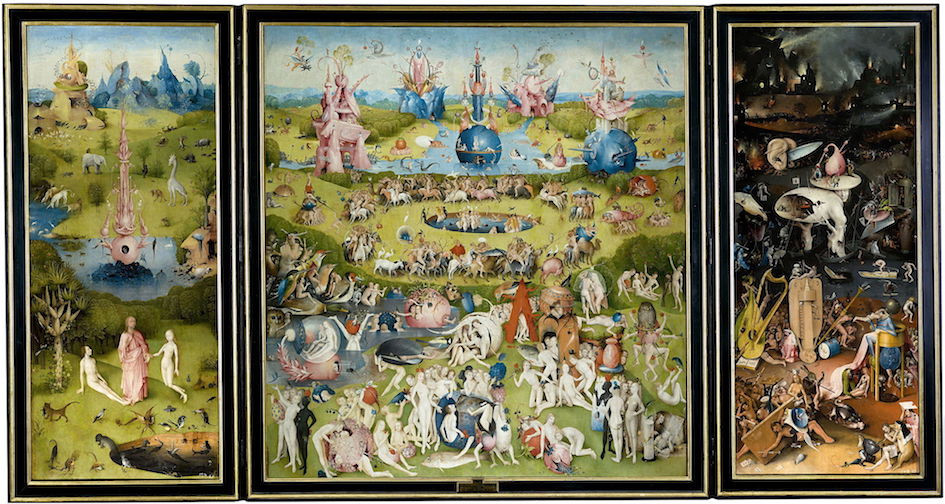

I first came across the term “epistemology” as a student in the 1990s, in a seminar on Michel Foucault’s Les mots et les choses (1966, translated as The Order of Things), itself a canonical example of art at the service of a ferocious philosophical project (Diego Velázquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas features prominently here). During that seminar, our Comp Lit assistant professor introduced the idea of an “epistemic threshold,” a series of breaks by which human consciousness shifts and develops. I remember the seminar room was flooded with spring sunshine, not unlike the Easter sun outside my window right now. This was, of course, a different, unhesitating sunshine, of hi-res 1990s quality. Innocently suggesting so much to look forward to. Basking in this dumb daylight radiance, our prof explained that, according to your respective socle épistémique, you might have believed that Easter was a time when bunnies roamed the Earth with big baskets full of multicolored eggs.

My assistant prof’s summary of Foucault’s assumptions is not as important as the efficacy of his theoretical picture – the portable mnemonics that still linger, a quarter century later. As a metaphor, a socle épistémique is more of a vertical elevation than the English “threshold” – socle can also mean “plinth.” The idea of an era standing clearly apart, perched on its epistemic pedestal, is catchy. All the more so as a pandemic raging around us draws brutal historical chapters, Before and After, with 2020 marking a biopolitical beginning of something we have yet to understand. Every now and then, time itself becomes less abstract than space. Some decades are more tangible in their differences than one city compared to the next. At this point, what those sun-kissed Foucauldian hipsters considered knowable, or knowledgeable, seems as quaint today as techno.

In today’s Berlin, the beating heart of ordoliberalism, multi-zillion-Euro stimulus packages are ratified, one after another. “Debts? What debts?” This is a rupture in the magnitude of the Easter Bunny paradigm. The U-turn is reassuring; it proves ruptures are still possible. By the time this essay is published, who knows how much will be left, epistemically and otherwise? In all likelihood, things will change. Among the things that will not, you might find the epistemic threshold of Contemporary Art as we know it. For all our investment in ruptures and disruptions, we have not moved on from any one belief system to the next, not in the last half century or so. Art doesn’t do clear-cut socles any longer, and even gentle thresholds are rare. The current state of affairs is so resilient, and has served the profession so well, that there is little incentive to engage in risky ruptures, of any kind whatsoever.

Which plinth are we discussing exactly? “The epistemology of Contemporary Art” does not imply a form of knowledge production that runs through the field as a whole, but the activities that constitute its signal effects, its distinctive identity, its discursive limelight as perceived from without, setting it apart from other economies. We do not mean the knowledge produced by invited scholars, nor the administrative apparatus that imparts rules and regulations. We mean the public events and exhibitions, the works assembled within them, and their immediate forms of mediation.

If, for example, you are arguing with a Kunsthalle accountant, about artist fees, say, and summon a municipal guideline to make your case, this becomes a clear-cut example of knowledge-as-power. By contrast, when we speak of art as an epistemological operation, we insist that there is no such power move at play. We as a field, by and large, insist there is no such thing as guidelines or facts that trump any other. Good art, we believe, does not succumb to a dialectic of realities and reality checks; all you have is a (temporary) foregrounding of materials, sensibilities, impressions that would never claim to be more than fragmentary, ephemeral. As a redistribution of knowledges possible, art can subvert prevailing certainties, but will not partake in producing them. Such is the suspension of disbelief that marks nearly every curatorial statement, museum press release, or artist talk under the sun.

When it comes to this Stedelijk show, the scope of realities represented is extraordinary and vast. Petals are collaged, racist prototypes are challenged, worker queerness emerges as a magazine. What is there to be known? Not about tulips, racists, and proletarians as such, but about their respective material renditions alongside other artworks that testify, in turn, to wartime massacres, drug abuse, colonial subjects and their commercialization, and more. How could I possibly claim that even here, amid this dizzying multiplicity, I can spot so much as a sliver of common ground?

To start with, none of these takes are framed as hard data, as claims you can disprove. Nor do any of the artists take a didactic shot at straightforward pedagogy, or at hard Left, let alone hard Right positions. As for the subtle platforms granted to marginalized forms of knowledge, they succeed in being generous without protagonizing anyone as genuine co-authors alongside the artists themselves. To be clear, I am not trying to be dismissive. I am attempting an empirical generalization of the show, a hypothesis you can disagree with.

Far from some kind of epistemic catastrophe, what the work in the show embodies is a professional ground that we have been meticulously producing and reproducing over time. A common ground where kaleidoscopic realities are summoned as open-ended materials for viewers’ interpretations. Curatorial language contributes to this pattern; when it strays from the descriptive, it implies that the work “addresses” and “explores,” that it “questions” or “departs from a question” – never replying to these questions, let alone resolving them. Answers are cumbersome when knowledge is one vehicle of creativity among many. The truth value of an answer cannot make up for the fact that it may be repetitive, or uninspiring.

All of which is particularly striking when so many artists in this Stedelijk collection are clearly experts in their own right, no less so than the philosophers and other specialists mentioned above. Many have expertly overcome academic, historiographic, political, and bureaucratic minefields to get to their material. Yet they will humbly eschew all claims to hard evidence, to the benefit of “zooming in on a representation,” at most. Again, expertise and hard knowledge are very much at play in a Contemporary Art setting already – they are simply not signposted as such.

If we compare this socle to that of Foucault’s poststructuralist generation, despite the energy invested in deconstructing boundaries between hard and soft knowledge, they did offer a broad set of daring parameters you could clearly disagree with. Their claims on the world are quite brazen. To a certain degree, Contemporary Art performs a comparable sleight of hand. For all our claims to be an unpredictable mess of anti-knowledge, our worldview on offer largely compounds the liberalism of the cosmopolitan middle-classes.

If Contemporary Art takes pride in its inability to lay claim to knowledge, art in general does not. You will find cases in point from Bauhaus to blockchain that have no qualms about positioned statements of fact. This is where the cropping and editing, showing and telling happens in the aim of something beyond an open-ended audience encounter. Depending on our historical circumstances, artistic intentions, and professional choices, an artwork can theoretically switch regimes at any given moment. Whenever institutional critique becomes an infrastructural proposal, whenever “playing” with a “representation” becomes a Representation, whenever archival reshuffling amounts to a new narrative, then we are moving beyond the willful unknowing of art today.

I have argued this before and have no intention to further rehash my arguments even more dogmatically than I have already. What might be more pertinent, at this point, is to ask what happens to said forms of knowledge production when faced with an epochal break, ushered in by means of quarantine, isolation, and access denied.

As shows are postponed and cancelled, one after the other, In the Presence of Absence becomes eerily prescient as a title. Many an exhibition will never see the light of day. Along with so much cultural, academic, athletic, and commercial programming that is now biting the dust. As we scramble to showcase everything online, we have all wondered whether art can be divorced from face time, from bodies moving through space. An old fart of my generation will forever be tempted to see all that digital stuff as second-hand, or artificial. When in point of fact, this is the way art is seen very widely, even primarily, at this point. In many places, remote viewing is so routine, it is barely noticeable. Many art fans across the world, geographically or otherwise distanced from museums, will only get a chance to see the work via PDFs and browsers, regardless of any pandemics. What the virus is doing to us, out here in the exhibition machine, is what many who wish to join us are going through at the hands of visa policies, neocolonialism, censorship, and crappy art schools.

Structural inequalities aside, digital natives have long argued that a virtual tour, a Vimeo link, and decent documentation all offer perks that a traditional show can only dream of. No sloppy tech, no sound bleed, no silly wall labels, no art snobs or chatty families. To be honest, even a catalogue scrivener rarely sees a show at the time of writing, only JPEGs and curatorial commentary, plus the Google searches and artist websites.

So why go to the party at all? One possible answer lies in the way knowledge is organized under offline and online regimes respectively. An online modus operandi arguably maximizes curatorial leeway. Once COVID-19 is dealt with, and hands are shaken at the opening, the work will individually convey some small measure of agency of its own. Under the conditions of embodied viewing, an artwork can often challenge its material surroundings to attain a micro-measure of semi-autonomy. For now, however, the PDF prevails, and the core concerns, the umph of the show, is defined by the team that assembled it. In this particular setup, the grammar of meaning-making lies firmly in curatorial hands.

Another reason to join the party is related to the above question of what makes Contemporary Art interesting to begin with. For all the things it can do virtually, the online sphere is where it faces unbeatable competition. Art can be catchy, entertaining, informative, but rarely with the efficiency of tweets, comments, headlines, Insta. Here’s our indeterminate mode of knowledge production reveals itself as a variation of post-truth, in an ocean of postfactual flux, indistinguishable from hegemonic forms of “truthiness” – but much slower at that. Consider our complicated timelines. Even if we tried to keep up with Facebook, we’d be hampered by the weeks and months, maybe years it takes to think, sketch out, rethink, assemble, edit, write the emails, find the curatorial spiel, secure the space, funding and equipment necessary, write up the mediation, etc.

Such is the saving grace of exhibition making. In times of crisis, our speed bumps are helpful. Not for nothing do people say one had better take a deep breath, before rubbing our ongoing tragedies in each other’s faces. My own writing these days is feverish, every paragraph tangled up in blurry panic. Perhaps this time lag is linked, in turn, to the ritualized funk of spatial experience – to art as payback for some form of temporal interruption. Even if the interruption in question is as banal as taking the bus to the Kunstverein, to see X, maybe alongside Y, and get annoyed as hell by the work of Z, all in the weirdly auratic setting of a specialized venue.

I guess I really am a crusty old git, still nagging you from that sun-filled room in 1995. That said, you cannot get any more nineties than someone passing off facts and histories as “facts” and stories. Someone claiming his knowledge is knowledge, and who camouflages mainstream liberalism as crazy shit. To move on, from this socle to the next, would imply hypotheses, indictments, projections, statements of fact. A mode of knowledge production that is as slow and rigorous as the infrastructure allows us to be. What kind of scenarios, however tentative, can we offer the economies, ecologies, infrastructures imploding around us? Our offline speed bumps are precisely what allow us the option of unapologetic forms of scrupulous knowledge. Art really would be in a position to occupy an epistemic plinth that over-stands and takes absence from the unending present.

Tirdad Zolghadr (b. 1973) is a curator and writer. Currently artistic director of the Sommerakademie Paul Klee in Bern, his curatorial work encompasses biennial settings as well as long-term, research-driven efforts, most recently as associate curator at KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlin, from 2016 to 2020. Zolghadr’s theoretical writing includes Traction (Sternberg Press, 2016), and his third novel, Headbanger, is forthcoming.